Written by: Yasmeen Ebada

Date: 2020-12-02

How one man’s film career helped shape his architectural design career

How one man’s film career helped shape his architectural design career

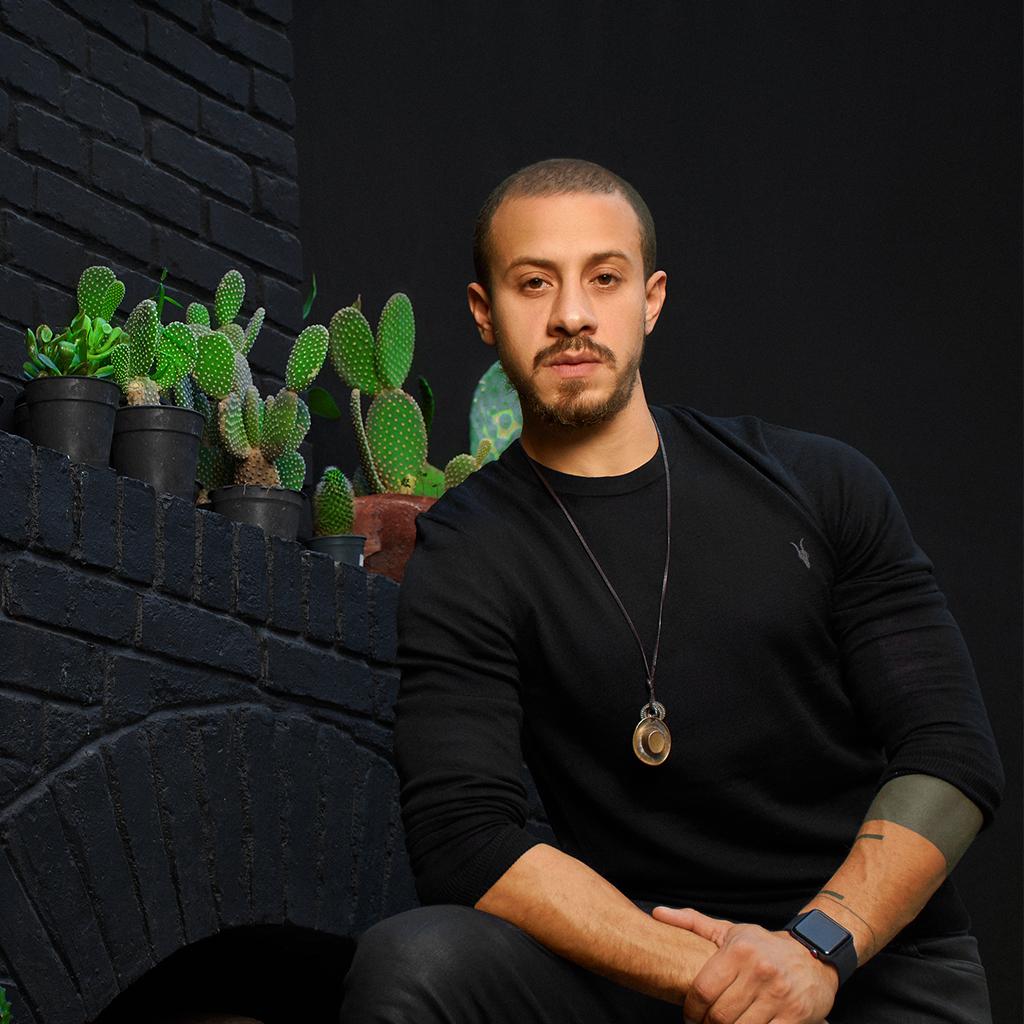

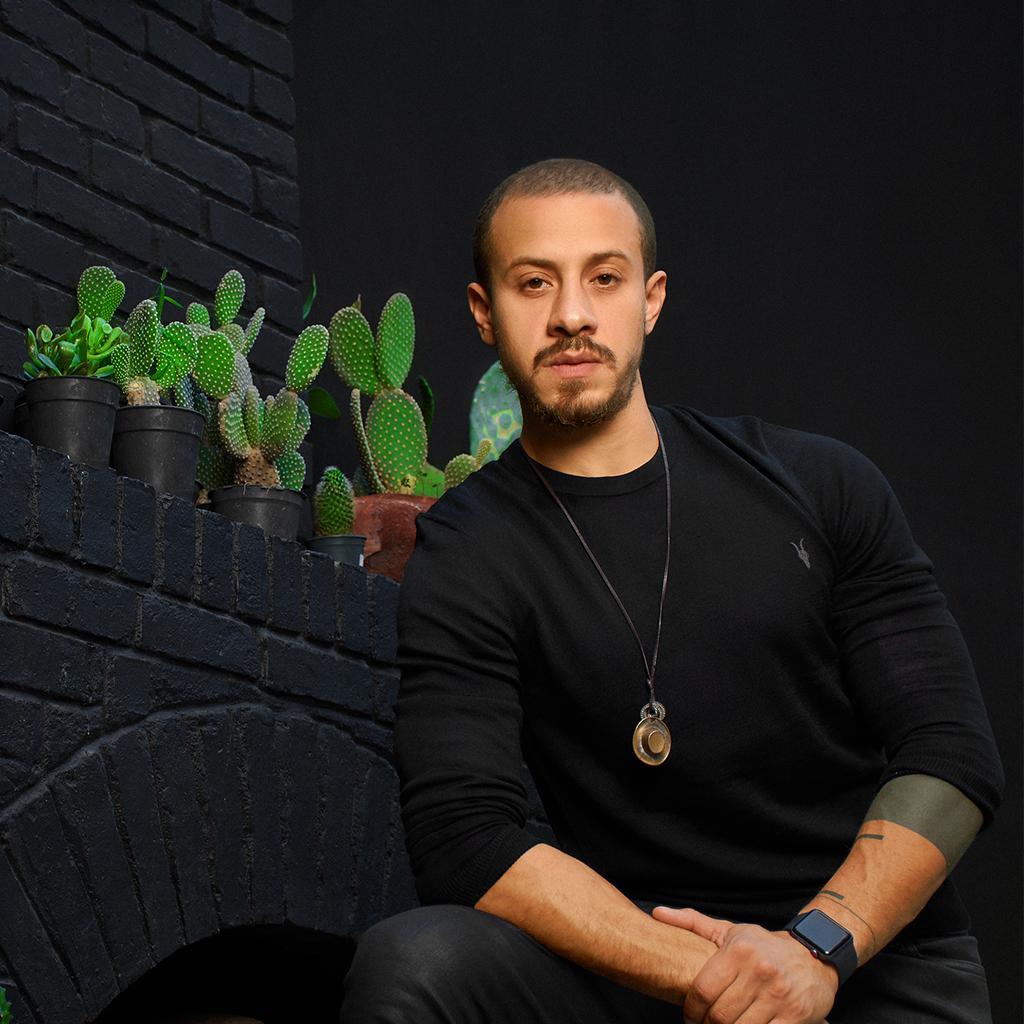

Successful interior designers and architects strive for diversity in their work and often attempt to avoid repeating the same designs. Mohamed Badie is no exception to this method. Badie chases new experiences every day because he believes it translates into his work and helps him achieve new design ideas in his projects. His projects are unconventional and bold, to say the least, and he challenges himself and his clients to push borders. He strives to execute unorthodox, impossible, and original work while aiming to provide his clients with better human experiences.

Similar to many Egyptians, Mohamed Badie picked mechanical engineering in college simply because of deep cultural roots.

While he was studying mechanical engineering at a private university in Egypt, he took a course on designing equipment and systems. This led him to switch to architecture.

However, upon graduation, he took a different career path and worked as a set designer.

“I gained a desire toward filmmaking while I was studying architecture,” Badie, the architectural designer, said.

As someone who always wants to participate in the universal language, the Egyptian film industry at the time was not fulfilling. He felt it was localized.

“I’d love to work in a world without borders or limits. The Egyptian film industry to me was full of restrictions and borders. We stop at a certain point. We can’t go extreme,” he said. “I believe that all of us are participating in a singular global culture. Design is a democratic platform for anyone in the world.”

He believed that the Egyptian film industry at the time was focused on budgeting and production.

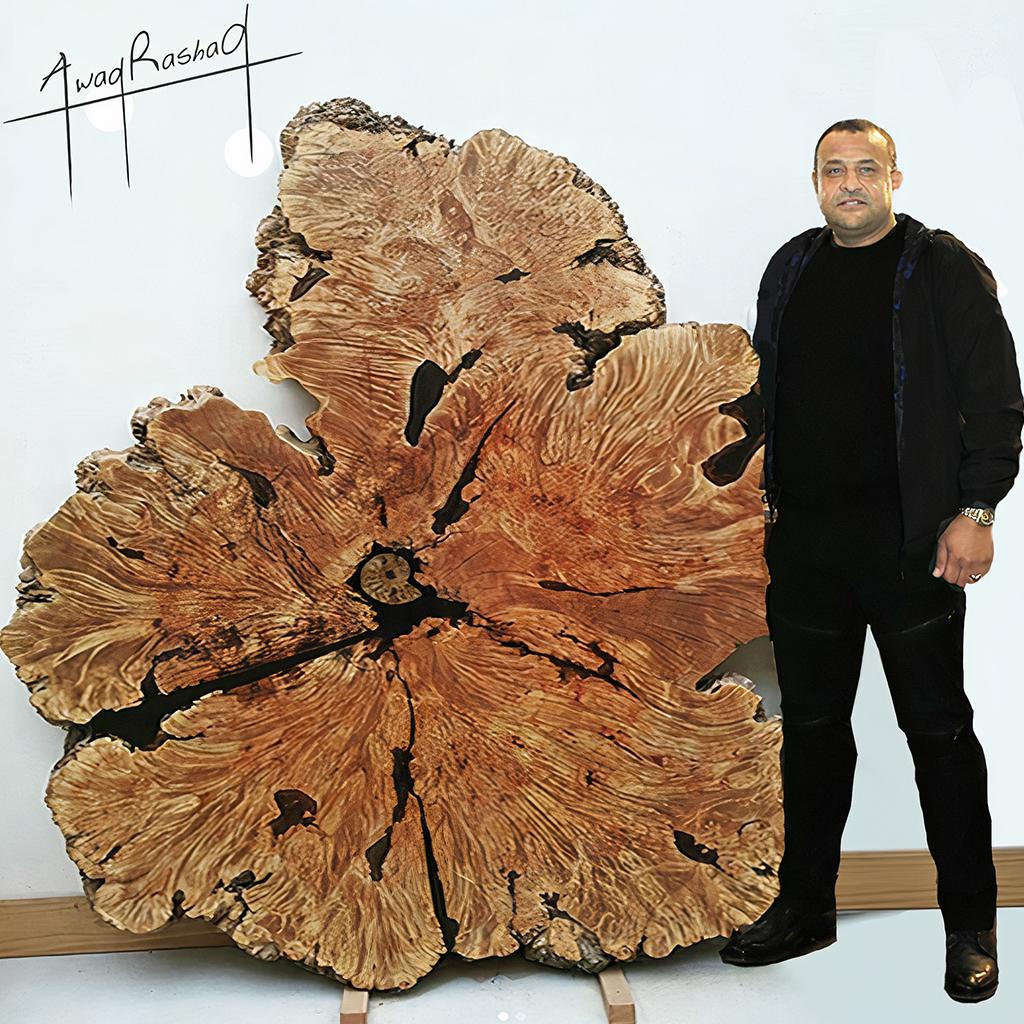

After three to four years, he left the film industry and opened a wood workshop.

Despite it being “one of the biggest failures” of his life, he learned the physical techniques of working with materials, manufacturing, and carpentry equipment.

Working in the film industry also helped him because it taught him how to humanize the spaces he creates.

“Our goal in the film industry is to spark the human experience,” he said. “We dress the room as if someone is living there. My designs are different because I learned how to add a soul to the space I create. People feel attached to my designs.”

The workshop also limited him because he was only working on manufacturing products.

“At some point, I felt I was more than just making a product. I’m a product designer. I always wanted to think on a bigger scale,” he said. “I felt like quitting the architecture and the interior design industry after this experience.”

His luck took a different turn shortly after he closed the workshop. He woke up one morning to an article written about the industrial space that he designed for his friend.

“I was one of the first people to introduce an industrial kind of atmosphere in interior design in Egypt. Those kinds of materials did not exist in our culture during this period,” he said. “I was depressed at the time, and that recognition gave me a push.”

From there, he started working on one project after another for a year and a half, working for different architecture firms. He transferred from one firm to another because he got fired frequently.

“I got fired because I wasn’t following the paradigm of the company, which I felt was not the right path for a designer,” he said.

Upon realizing that he couldn’t work for anyone, he opened his architectural design firm. It happened gradually. He started in a small shared office.

“I stepped into the architecture world with a set designer’s perspective,” he said. “I thought everything I was doing was bullshit. I thought I wasn’t going to achieve anything. At the time, my work was not appreciated like it is today.”

People thought his ideas were unorthodox.

“My projects are bold for a conservative culture. I create original designs and new experiences,” he said.

In Egypt, the interior and architectural design industry is about styling Badie says.

“In design language, ‘styling’ means you go back to history and you get inspired, but it’s a short-lived inspiration,” Badie said. “We follow more than we create because we fear the unknown. This is called copying.”

According to Badie, a designer should never replicate history.

He stayed in the US for a year and has executed several projects. It was another turning point in his career.

“I got to know who I am, what I want, and what I am capable of. I left my comfort zone, and I explored. You either survive or you don’t, and I did,” he said. “I felt like I was naked, and I was finally starting to put on clothes.”

His work was appreciated over there, and that made him recognize that he could produce global products. This gave him hope, so he returned to Egypt.

“This made me recognize that if I design a house and place it anywhere in the world, it would work,” he said.

He returned and started his firm once more. He started growing gradually again while publishing his projects.

“Achieving original designs is not an easy job. I have to be a unique individual to be able to produce unique designs,” he said. “You have to practice creating original experiences to avoid creating repetitive experiences. This translates into my designs.”

According to Badie, falling into certain patterns prevents us from achieving the unknown.

Repetition in architecture or interior design is the best strategy in terms of a business standpoint and for gaining a profit.

“From a business standpoint, my philosophy is horrible in terms of gaining a profit. However, it helps me to live happily, to live originally, and to enjoy every little moment,” he said. “Being rebellious is not just for the sake of changing the paradigm. The human experience needs to get better. That is why you are here, and that is how you grow. Designing is not about solving a problem. When I’m designing your house, I’m not solving your problem. Instead, I’m helping you achieve better human experiences.”

Badie gets his design inspirations from the human experience.

“I am a perceptive guy, and I enjoy watching human behavior. If I understand the human experience well, I will build and design anything,” he said.

One of his biggest projects is executing the interior and exterior design of the pavilion for Volkswagen in Capital Business Park (a business hub) and in Cairo Festival City Mall.

“It was a big challenge because it was kind of a street scene. I was able to create that whole new experience of when you step around the pavilion you see something different. It’s a fourth-dimension kind of experience,” he said. “There’s something unknown about the design, and it forces you to stop. It is weird, dynamic and original.”

This was Badie’s first pavilion project.

Regarding design styles, Badie tries to achieve neutrality in any kind of space.

“The digital age is reshaping human experiences. The design in the digital age must be casual. There are no rules to follow and no past to live by. The digital age is shrinking everything. Casual means you could do whatever you want,” he said.

Badie believes that designers should be selfless.

“I push my clients to be present. I push them to kill their patterns, to kill their past, and to kill the cheap replica of what they are accustomed to,” he said.

Badie does not have career goals because he likes to live in the present.

“Working on the contemporary criteria for the right moment helps you build a future,” he said.

The global pandemic made people reevaluate their living spaces.

“Now you only have one option. People are starting to specialize each space in the house,” he said. “The value of the house has increased. The living space is not just a living space anymore. People want an experience.”

Badie is his own mentor. He believes if he has a mentor in architecture or interior design that means he is styling and not designing.

“If I follow a specific architect or have interior design role models that means I am following and replicating their work,” he said.

In the industry, he believes that trends are the most dangerous traps for designers to fall into.

“Designs must represent the right time in history. If you brush off a vase, you should be able to understand the time period of when this vase was built and designed,” he said. “Marking the right moment in history is a huge responsibility. This goes against the idea of trends. Trends die. A trend is a cheap replica of a paradigm.”

It is crucial in this profession to understand the client’s character. Badie can read someone from the way they are dressed, how they interact, and their body language, and he can tell if the client is conservative or not.

“I try to push my clients’ borders and to get them out of their comfort zones by implementing bold designs. There are many arguments during this process because a big part of my job is persuasion. A potential client pushes me out of my borders as well,” he said.

Badie pushes his clients to be themselves.

“An architect or a designer’s work should represent the client’s character,” Badie said.

His advice for young designers is to invest time in developing strong software skills.

Badie has also taught an interior design course at the German University in Cairo.

“We wanted to provide students with a professional, real-life experience of architectural designing,” he said.

When he is not working, Badie loves to spend time in nature.

“Achieving neutrality in interior designs helps me become more of myself. Interior design made me fall in love with nature,” Badie said.