Written by: Jehan Selim Harney

Date: 2017-04-01

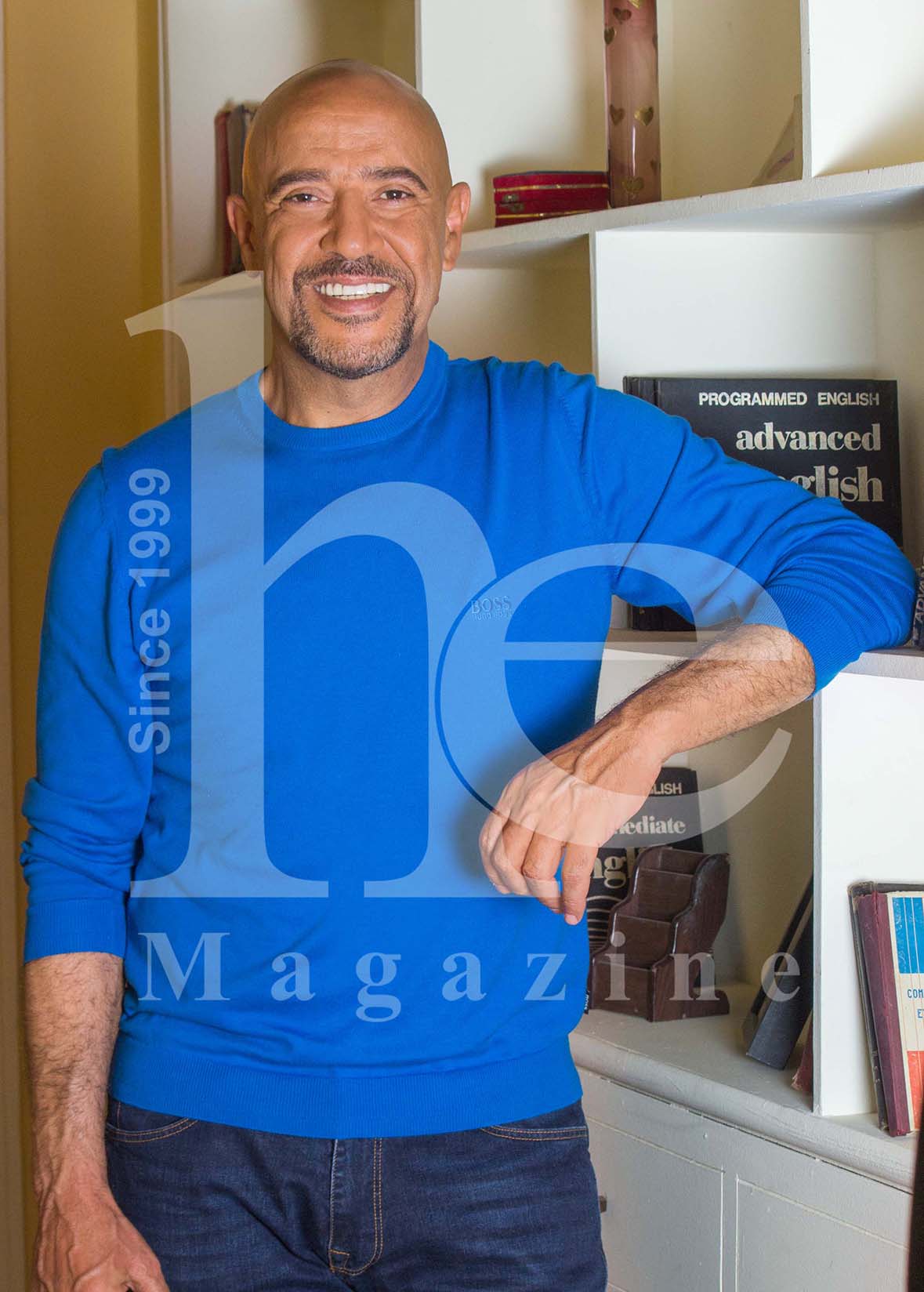

Comedian Superstar Ashraf Abdel-Baky on Mission to ‘Revive Egypt’s Theatre’

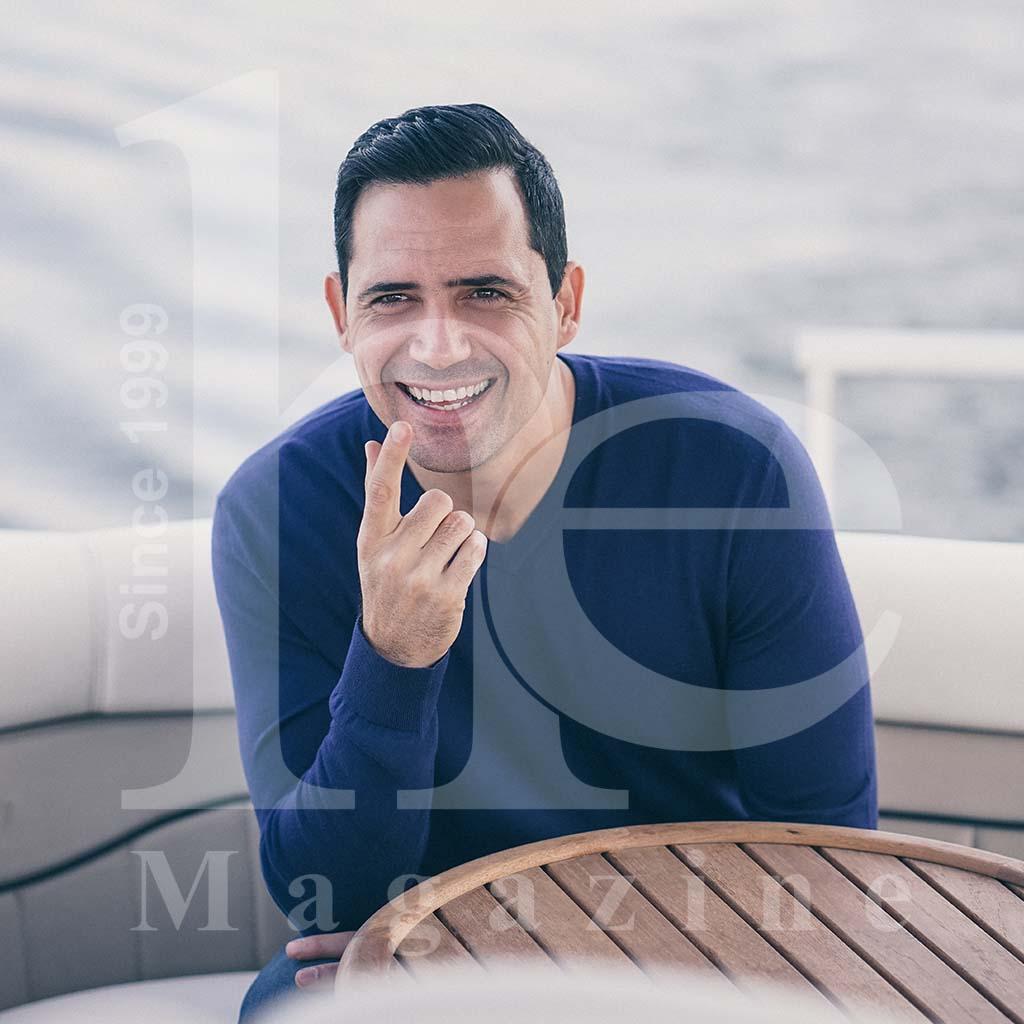

On a mild Tuesday afternoon at a production studio in Giza, comedy star Ashraf Abdel-Baky rehearses his role as Abdel-Aziz for the new Ramadan series, Zizo’s Family. Dressed in a crisp light blue dotted shirt and grey khaki pants, Abdel-Aziz enters a house where his family impatiently awaits him. His mother-in-law, played by actress Shirine, bursts into his face asking: “Why haven’t you convinced the old lady to sell the damn house if it is worth two million Egyptian pounds?” He pauses and then with a sceptical smile he confidently responds: “Because the land of the building is now part of a city renovation zone which has pushed the price to 4.5 million pounds.” Suddenly, the family is elated and the mother-in-law, who apparently rarely praises him, then changes her tone: “Oh, Abdel-Aziz, you are such a genius!”

In reality, 53-year-old Abdel-Baky’s body of work speaks for his “genius”. The physically fit comedian acted in 52 films, 350 series, and 15 plays, including the very popular Egypt’s Theatre, and presented 20 TV shows, including the current Live the Nighton DMC. Since the age of 16, Abdel-Baky acted in nearly 80 amateur theatrical productions. He giggles, “I sometimes directed, and even composed and edited the music and designed the set of those amateur plays.”

After he performs his part on the set of Zizo’s Family, Abdel-Baky goes outside for fresh air. He sips anise-mint tea as he reminisces about his childhood that helped shape who he is today. “My father often took me as a kid to the theatre where I saw many plays.” He recalls he was “hooked on Adel Imam’s The Witness Who Saw Nothing,” and was “mesmerised by the spotlight on the actor who moved an entire audience’s emotions.”

That kid then had put his passion into acting by participating in school plays, while on the side helping his father in his contractor business. Eventually, Abdel-Baky opened his own contractor business, hiring 33 workers at the age of 18. After graduating from Ain Shams University’s Faculty of Commerce, he opened an aluminium factory and also continued his acting. His passion quickly paid off when director Raafat Al-Mehy discovered him and introduced him to the cinema industry. From then on, Abdel-Baky became a quite busy actor and had to close his factory.

In the midst of living and talking about the past, the director calls Abdel-Baky for his next scene. He quickly changes into a more comfortable outfit: a dark blue sweatshirt and a chequered blue pyjama pants. In between takes, he reminds the cast members and production team, “Don’t take long in the shoot, please.” He explains: “I have healthy snacks for you today!” His assistant prepared cheese sandwiches made with lettuce, watercress, and parsley along with fresh veggie bites and fruits.

Abdel-Baky tries to eat healthy on the set where he works nearly 12 hours a day. For the past 25 years, he has been eating small meals five to six times a day after he was diagnosed with stomach ulcers. Binging on veggies is not that difficult for him either, given that his 21-year-old daughter has been vegan for three years. “No wonder I am in this shape today,” he laughs.

And, about his well-toned body, Abdel-Bakry says it’s from “doing lots of handy work”. The comedy star has a decent size workshop in his New Cairo house. It looks like typical state-of-the-art workshops that are showcased at Sears Department stores in the United States. On his vacations to visit his siblings in the United States, Abdel-Baky enjoys shopping for handyman appliances and tools such as a sliding compound miter saw that he bought at ACE. His bulky handyman purchases incite a “puzzled look on the faces of customs agents at the Egyptian airport.” He laughs, “They keep wondering what the hell does an actor do with such handyman stuff?”

Whenever Abdel-Baky is not occupied with acting, he loves his alone time with his handyman tools in his own workshop. “I make everything you can imagine,” he says. He loves to decorate his home, which has a very modern style. I couldn’t help but notice his extra-large open and sleek looking black and white kitchen. He laughs, “That’s only for entertaining guests.” He continues, “The real molokhiyah kitchen is elsewhere, and it is rather closed for doing real cooking!”

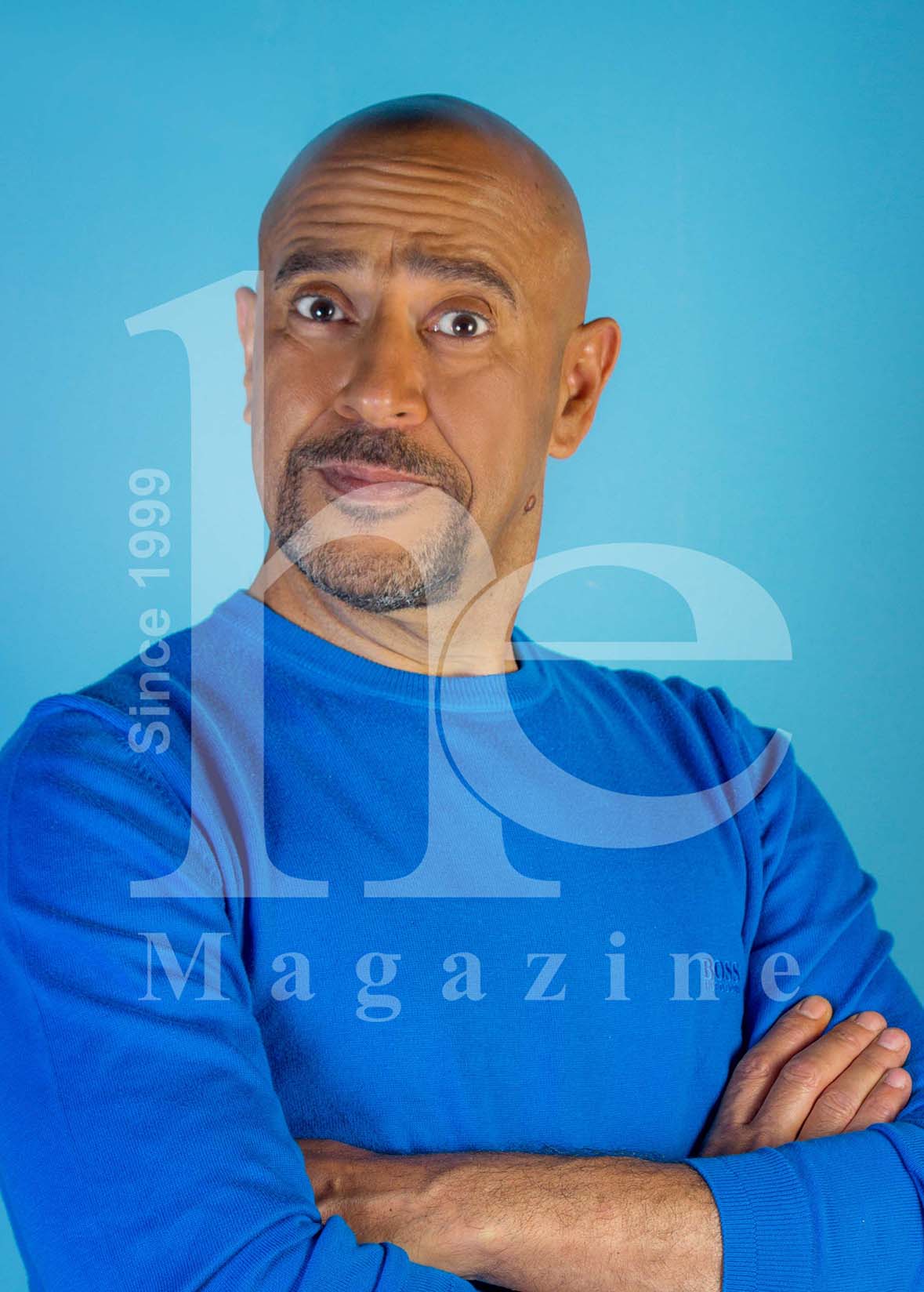

As Abdel-Baky continues to talk, he orders more herbal tea. He watches production people move boxes inside the set to prepare for the next scene. He reminisces about the “old days” when families often took their children to the theatre. Slowly, he emphasises: “We are a country of more than 90 million people. We need more theatres. They are a common indicator of the advancement of any culture.”

The comedian star understands why theatres are not common here today citing, “The popularity of mobile phones in Egypt in 1996 has allowed people to access all types of entertainment.” “That made sense,” he continues, “particularly as mobile phones take nearly EGP 12,000 of their income.” Also, malls, he adds, have provided people the “space to hang out at their convenience, whereas theatres open doors too late for families after 11pm for nearly four hours straight as they sit in uncomfortable seats.”

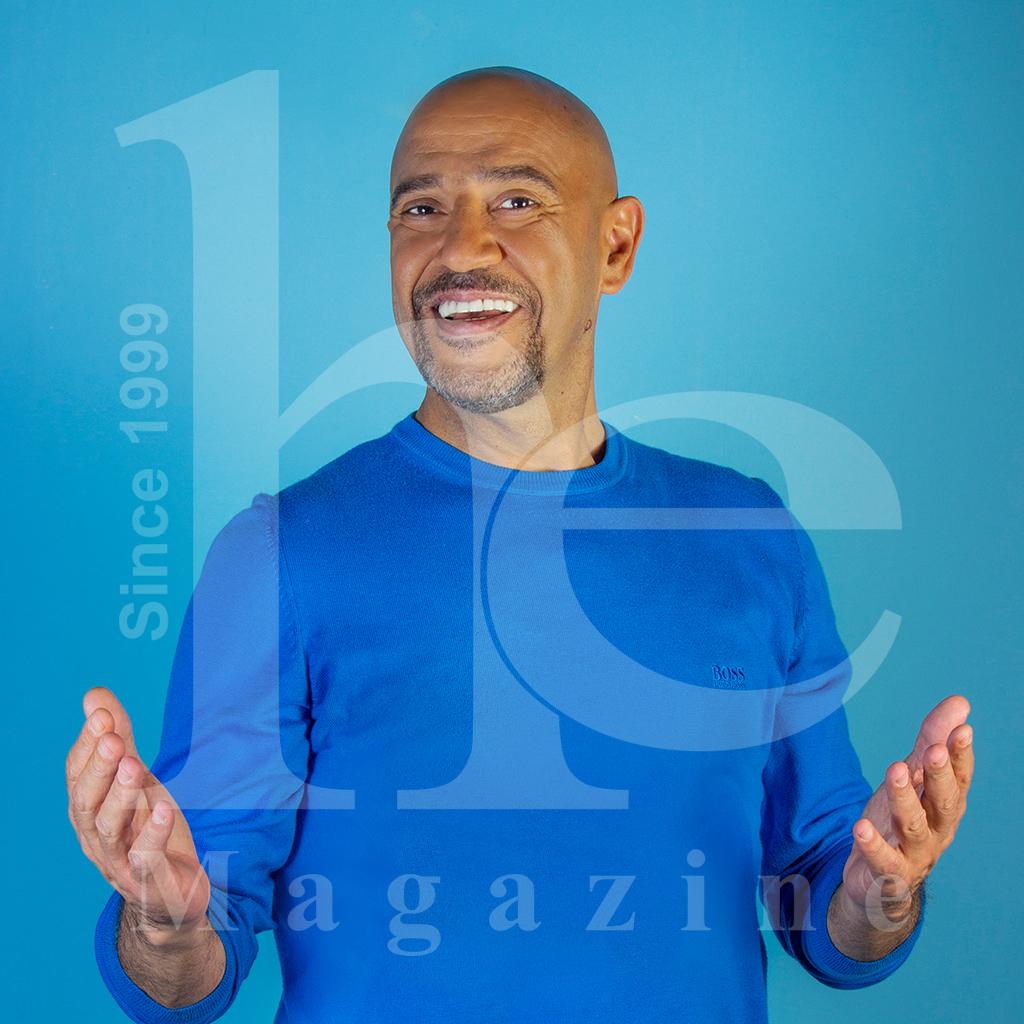

Instead of succumbing to reality, Abdel-Baky decided to change it. He lights up a cigarette and says with a smile, “I thought why not make one-hour plays with condensed laughter.” And, his idea paid off when he started Masrah Masror Egypt’s Theatrein January 2014. It was a new kind of theatrical play that runs weekly as episodes. Each episode has a new title and subject, presented in an entertaining yet cynical way relying on actors’ improvisation in nearly 80% of its content. It boosts “regular and new faces in each episode”. The popularity of Egypt’s Theatreattracted television as well. First, Al-Hayatchannel aired it under the title of Teatro Masrand then MBC Masrpicked it for a third and fourth season under the present name of Egypt’s Theatre.

You would think the comedy superstar would capitalise on the popularity of Egypt’s Theatreby focusing the spotlight mainly on himself. But, in each episode, Abdel-Baky appears briefly playing a small role, giving many the chance to bask in the limelight. “I want a new breed of actors to reinvigorate theatre in Egypt and make families want to go back to it for many years to come.”

In a way, that is Abdel-Baky’s legacy which almost didn’t happen had he not passionately believed in it. For seven years, Abdel-Baky brought his idea around but “it was constantly and flatly rejected by producers”. He then decided to give it a shot by making it come alive in 2011 on a stage he built himself in his Mansouriyah home.

Around that time, Egypt’s economy and mood were in a sombre state after the 25 January Revolution. Nobody was investing much in the arts or theatre. The resourceful comedian transported the actors and production members to rehearse short plays he wrote and directed himself. “We eventually had four play episodes under our belt as a pilot to test with producers,” he laughs, “and the rest is history.”

In the midst of our conversation, an old man, who later on I found out had played a side character in one of his plays, interrupts Abdel-Baky. “Thank you,” he says as he shakes his hands, “you revived our love for theatre.” Abdel-Baky is thrilled to hear feedback like this, but he wants to keep the momentum of Egypt’s Theatregoing.

Abdel-Baky realises his breakout stars someday are expected to leave when they get lucrative offers elsewhere. He firmly defends them, “and they rightfully deserve a higher pay for their talent.” Whenever that happens, he says, “I approach the TV network to pay them more and they do.”

Similarly, he hopes some of the new faces, though they appear usually once in Egypt’s Theatre, actually make it so that his theatre vision can live on. “I can’t keep new faces longer because I need to provide as much chance for others to have their big moment on stage and in the public’s eye.” In a way, Abdel-Baky’s dream to revive theatre has become a school for breeding strong actors and a workshop for training others. “This is about the future of theatre. It isn’t really about me,” he reflects.

Ironically, Abdel-Baky’s life could have taken a different turn at 25 when he could have joined his older brother who has been living in the US for nearly four decades. After he graduated from the Faculty of Commerce at Ain Shams University and attended the High Institute for Theatrical Arts, he wanted to study acting in the US. He was accepted at Northeastern University in Boston, MA. “But I couldn’t do it,” he pauses, “the life routine there didn’t resonate with me,” he concludes. “Though my brother assured me as a contractor I can make a lot of money in the US,” he jokes.

The father of four still visits the US to see his brother and shop nonstop for more contractor tools and appliances. Once he got bored and decided to take English and acting classes. Neither the teachers nor students knew about his background but were captivated by his talent and humour. At the end of the course, he shared his secret with them. “I showed them my work on YouTube, and I got the last laugh; their reaction was priceless.” This summer, Abdel-Baky hopes to continue his learning journey by attending the New York Film Academy.

Around sunset, the actor joins the Zizo’s Familycast for a delicious creamy ringa. He says his mind is always working, buzzing with ideas. “I just can’t take a break,” he giggles. Once he couldn’t survive a four-day vacation in Sahel with a group of actor friends. “I had to cut it short,” he says, and he drove into the sunset back to Cairo without notice. “I missed working. I missed creating things!”

The actor started nearly 200 business projects, including an Edible Arrangements type of business that didn’t last beyond a year. He eats a bit of ringa with his cast members and bites on a scallion as he reflects on his journey. “I learn from any setbacks. I am proud I did it all and take full responsibility.” He then pauses as he gently watches the faces of his cast and crew members, “We live only once.” But Abdel-Baky knows at least when to stop. “I definitely cannot be a police officer,” he laughs.