Written by: Jehan Harney

Date: 2016-10-25

To Fahmy, his success as an actor is not that which really defines him as a person. He rather proudly considers himself a “seeker of knowledge” and has been ever since he was a child.

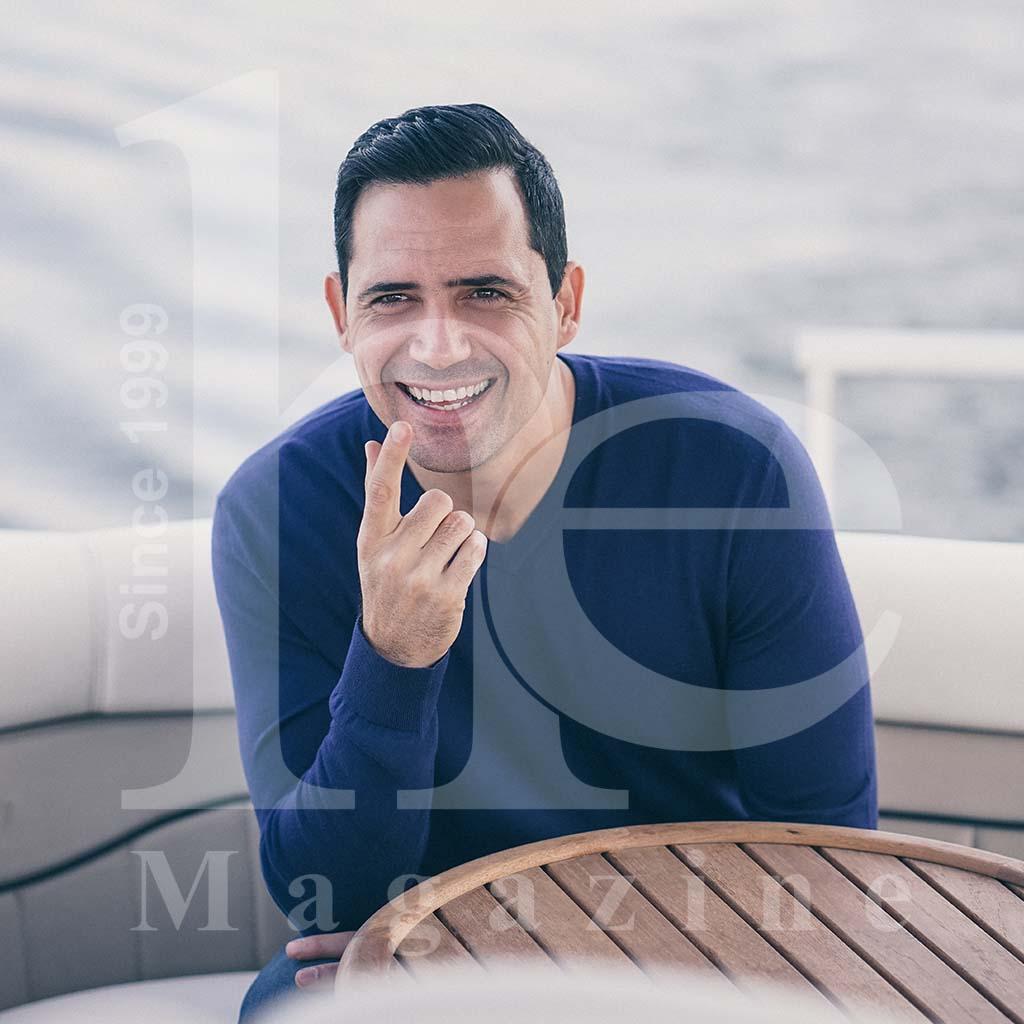

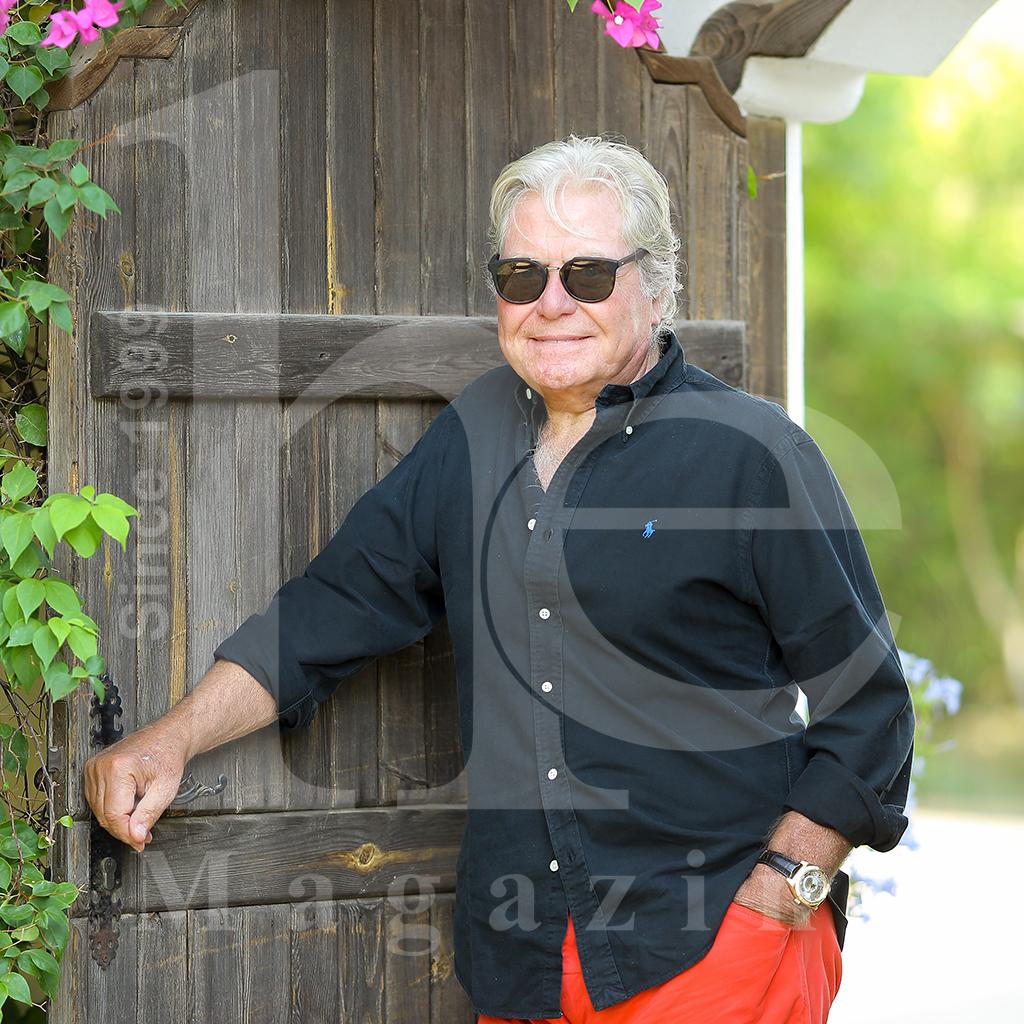

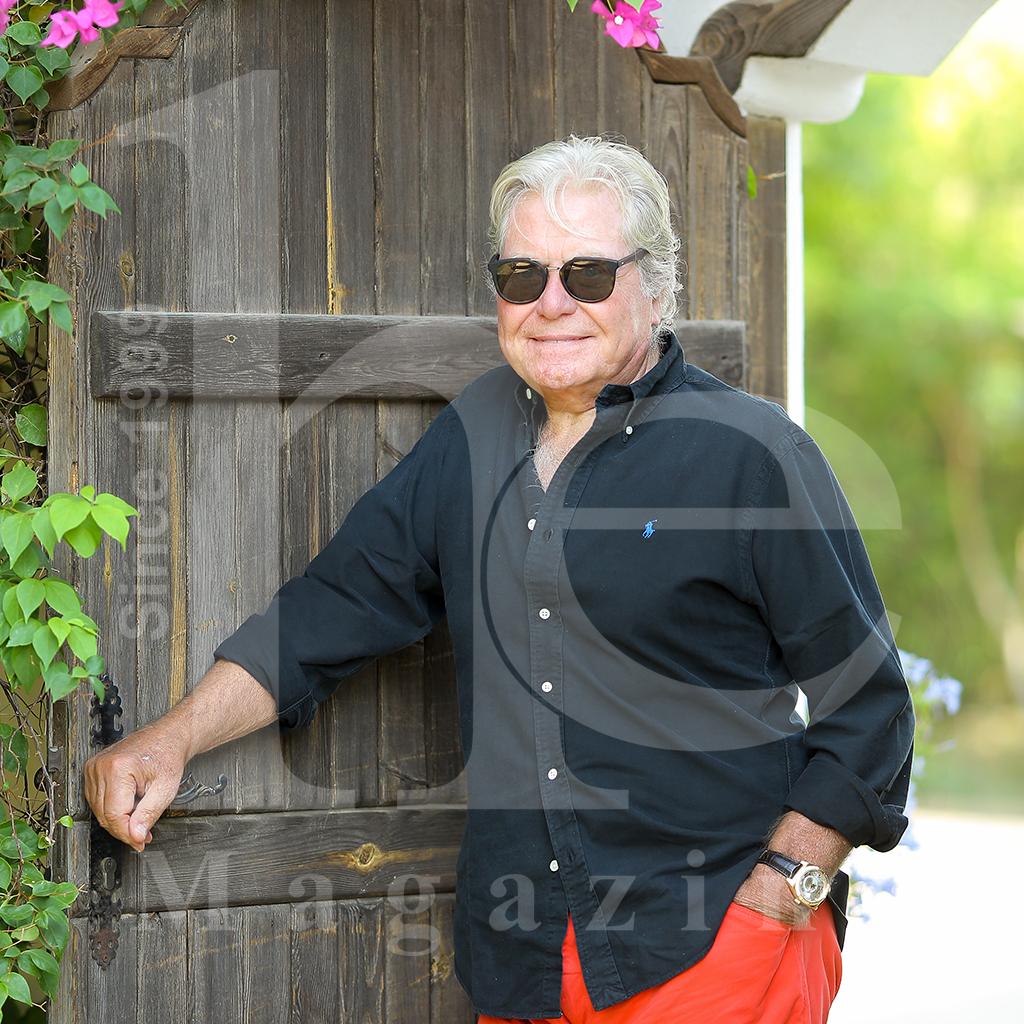

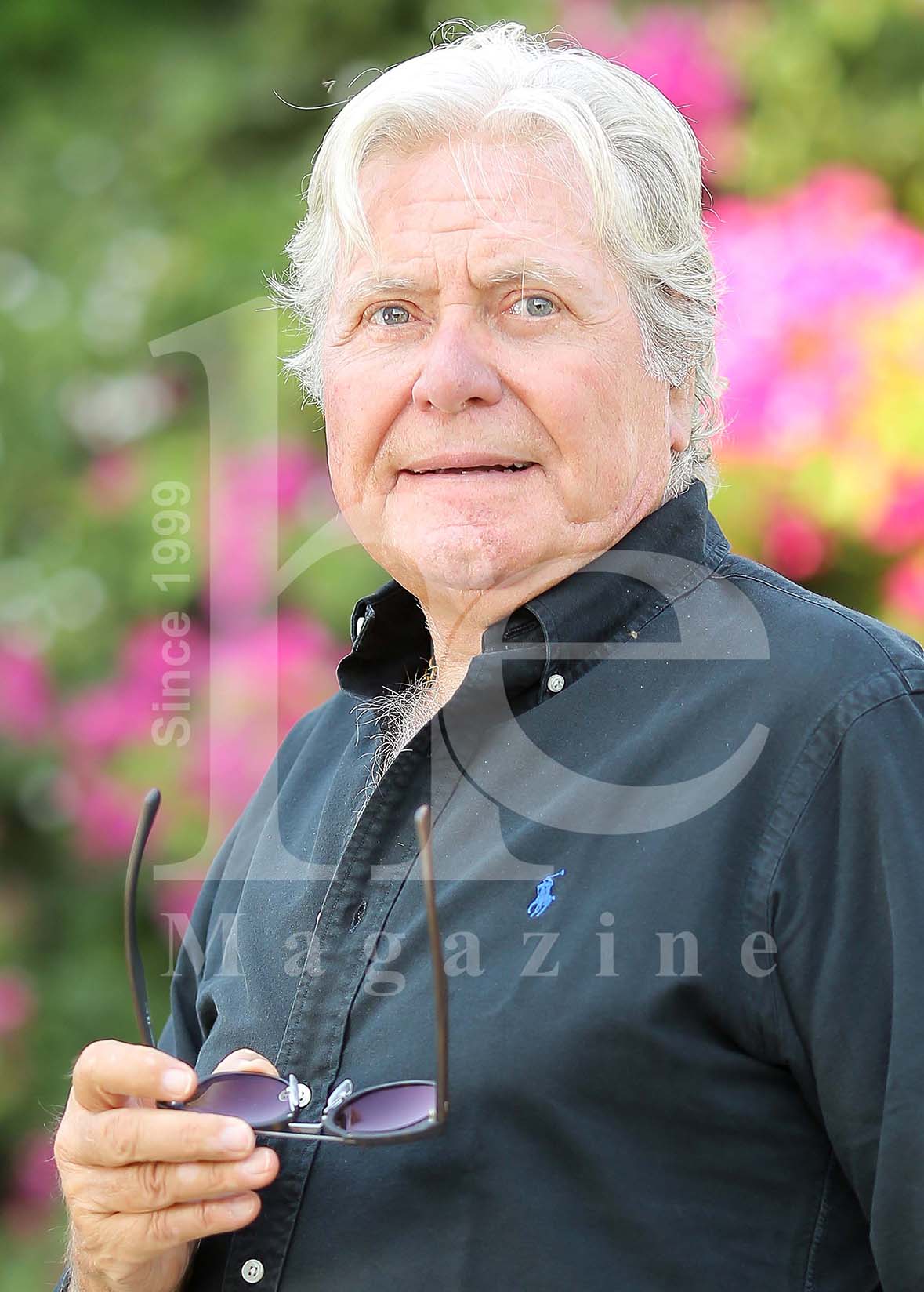

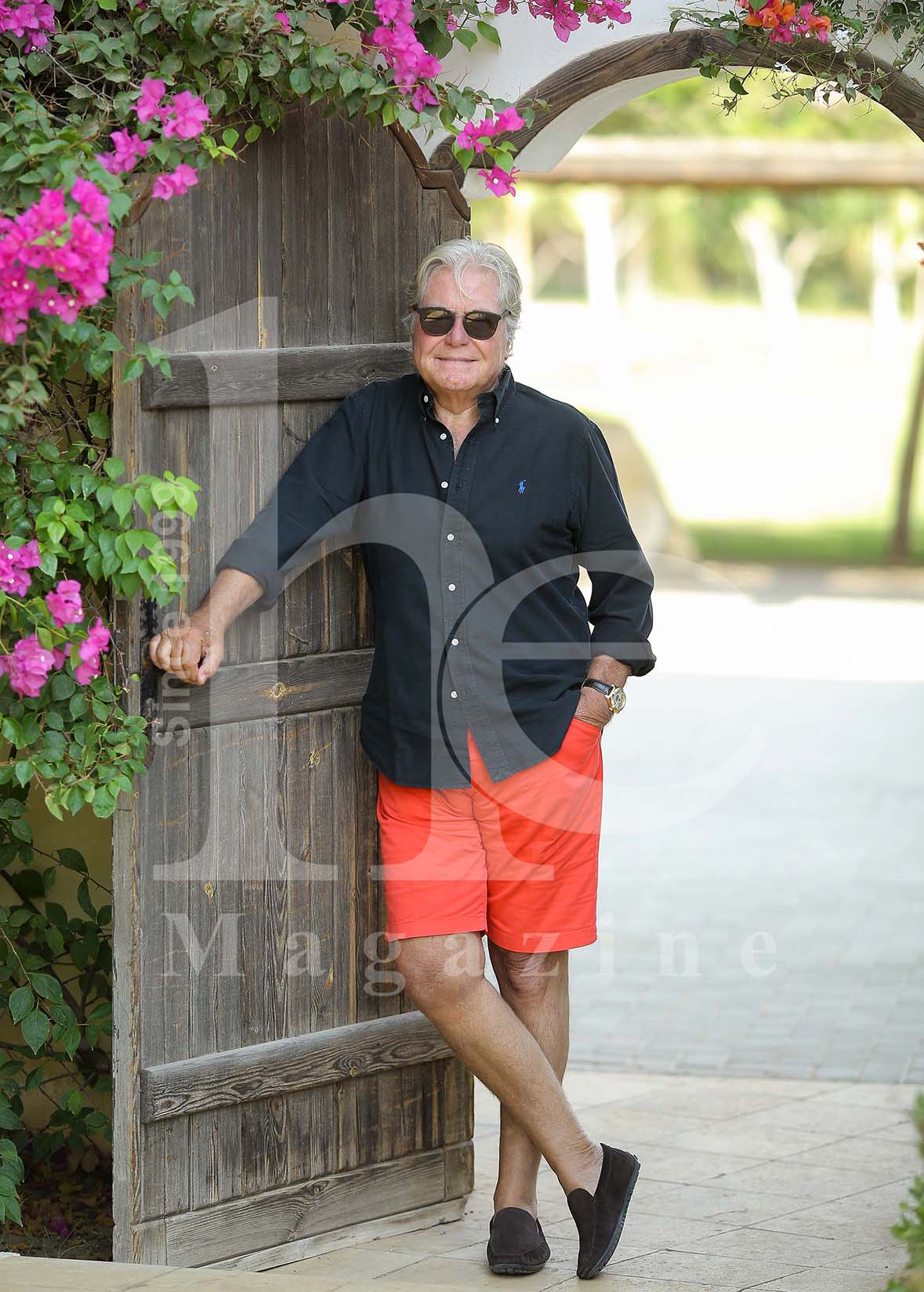

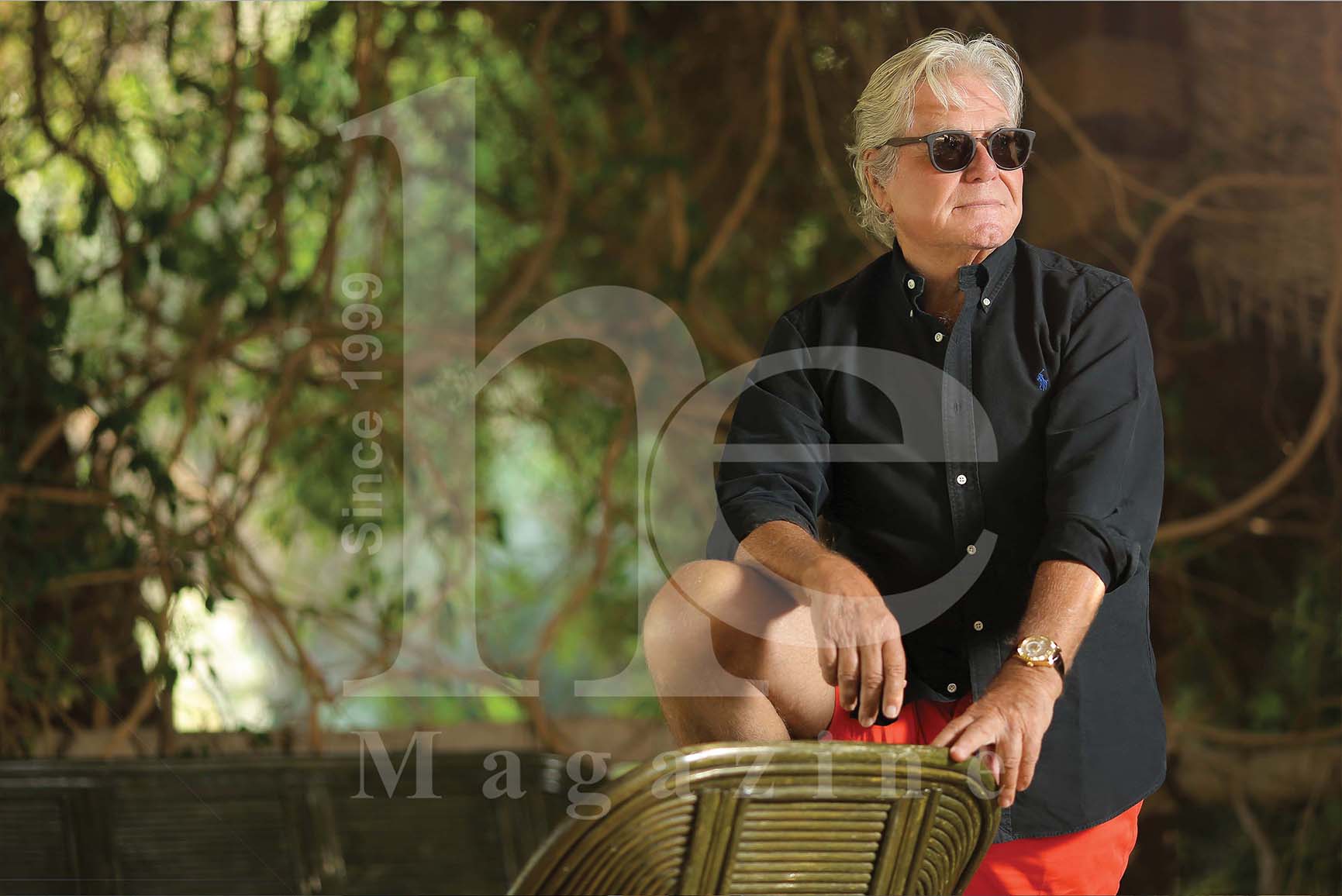

Amid the crowds at Ramses Station on a Monday afternoon, movie star Hussein Fahmy takes a break at a cafe on the second floor. He is filming an episode on the history of railroads for his weekly show “Zaman”, or “Time”, on Al-Ghad TV. “I am intrigued with the concept of time and how we constantly move through time as it stands still,” Fahmy reflects. And he really does take timevery seriously. “I consider myself a visitor on this earth, and I believe there is only this life to live—just this one—even though other mythologies and philosophies may suggest a second or even a third afterlife.”

And in this life Fahmy tries to make the most out of his time. The accomplished actor has worked in film, theatre, and television for more than 45 years, appearing in more than 100 movies and counting. But to Fahmy, his success as an actor is not that which really defines him as a person. He rather proudly considers himself a “seeker of knowledge” and has been ever since he was a child.

“Growing up, we had an Encyclopaedia Britannica in our home,” he reminisces as passengers at the station walk by and greet him with a smile. Hussein smiles back and continues, “Whenever I had a question about anything, my parents always told me to check out the encyclopaedia. Each time I looked up something, I became more and more intrigued by many different things.”

Today, Fahmy still continues his passionate quest for knowledge. He spends at least two hours daily reading books on philosophy, history, psychology, sociology, and his favourite discipline: politics. Fahmy also practises transcendental meditation. “It helps me to understand myself and the universe around me better,” he says. In the 1960s, Fahmy learned about this spiritual practice in Los Angeles from the well-known guru Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. Everyday, Fahmy disconnects with the outside world to focus inward by meditating at home next to his fireplace or in the garden by his birds and five German Shepherds.

Dressed in a navy, half-buttoned shirt and summery, grey linen pants, Fahmy calmly leans back on his chair. He recalls his early days in the US and their profound impact on his life. He graduated from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) with a Masters of Fine Arts in 1965. In those days, Fahmy became heavily immersed in US politics. “I protested in rallies against the Vietnam War and the assassinations of Martin Luther King and John F. Kennedy and took part in the Hippie movement.”

Throughout these protests, Fahmy met with the philosopher, political activist, pacifist, and Nobel laureate Sir Bertrand Russell. His writings championed the humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought that Fahmy was passionate about. The actor even participated in protests to demand a “fair minimum wage for Mexican workers in the US”. Some people remarked, “Why do you care about the Mexicans!” To which he responded, “I am a humanitarian who is part of the whole world and not just a particular country or race. I care to better the world anywhere I go.”

Indeed, his humanitarian ideals and passion propelled him to be the first United Nations Development Programme Regional Goodwill Ambassador for the Arab States from 1998 to 2006. “I wanted to motivate people to act in the interest of improving their own lives and the lives of those around them,” Fahmy says, as he leans forward to sip his cappuccino.

In 2007, the movie star was named the first Special Olympics Ambassador for the Middle East and North Africa Region. The Special Olympics is the world’s largest sports organisation for children and adults with disabilities, providing year-round training and competitions to more than 5.3 million athletes and sports partners in nearly 170 countries.

Fahmy was excited about his earlier travels to the US. “I was going to live in the biggest democratic country on earth. Who wouldn’t love that?” he exclaims as he stares like a child with excitement in his eyes. But unfortunately, his image of American democracy was shattered after several experiences.

“In the US, if you have an opinion that upsets the majority, then your opinion might as well not be heard,” he continues. During the 1967 Arab-Israeli War, Fahmy raised funds from the Arab community in Los Angeles to place an expensive ad in The Los Angles Times. He passionately says, “I wanted to highlight the underrepresented Arab view in this conflict.” Unfortunately, the newspaper flatly denied his request.

Nonetheless, the outspoken actor continued his fight to make his views heard through student debates, writings in student newspapers, and protests. He jokes, “In those days, I was often called anti-Semitic.” Fahmy would then responded to his “haters” by saying, “but I am actually a Semite… Now let’s discuss the real issues.” He says that often got some ears to listen to him.

As he watches people walking by in the train station, Fahmy recalls his first experience of culture shock upon his arrival at UCLA. “I noticed Hebrew name plates at the registrar’s office. I then asked, can I write my name in Arabic? But they said “absolutely not!” Nearly 15 years ago, the actor, who was appointed as the President of the Cairo International Film Festival in 1998 to 2001, attempted to organise an Egyptian film festival in New York. At the last minute though, he says he “received a call that the festival can’t happen,”referring to the influence of the “Jewish lobby” in blocking his efforts.

After his experience in the US, the hard-headed actor realised that “there is absolutely no perfect democracy”. He explains, “America tailors its democracy to suit its system. Similarly, we in the Middle East, particularly in Egypt, should create a democracy tailored to our needs and circumstances. Nobody should tell us or push us to do it.”

The movie star here refers to the clash of internal and foreign forces that played out discretely during the January 25 Revolution. Fahmy did not join the protesters then, though he did in the past against former president Anwar Sadat at Tahrir Square.

“I had many questions about the January 25 Revolution,” Fahmy nods. “We wanted to change as Egyptians and have our freedom, but foreign powers had other plans. They wanted to throw the region into constructive chaos and create a new Middle East, broken into smaller states.” He describes the attitude of US President Barack Obama as “arrogant” for calling on then-president Hosni Mubarak to leave. “Only Egyptians can tell their president to leave,” he affirms.

With the involvement of various foreign forces in Egypt, he feels that such a revolution was not “pure” although Egyptians had “pure intentions”. He refers to the “interest of Israel in the region from the Nile to the Euphrates” and the “ultimate plan of foreign forces to destroy Egypt and have the Muslim Brotherhood, which did not have the interest of Egypt and the Egyptians at heart, rule what’s left of it.”

Fahmy was concerned with how “the US Congress, which represents the American people, has been marginalised by the Obama Administration and by US Ambassador in Cairo Anne Patterson, who sent erroneous reports on what was happening in Egypt”. Fahmy therefore made it his mission to set the record straight.

“I met with Ambassador Patterson twice at meetings of ambassadors and politicians,” Fahmy says. “I told her that I am neither a politician nor a diplomat, but I am an actor who believes she is incompetent for relying on incompetent people like the Brotherhood.” He told her that “the Obama Administration is sponsoring terrorism by encouraging terrorists,” referring to the Muslim Brotherhood, which was on the US list of terrorist organisations. Even though Patterson suggested they had come to power through elections, Fahmy insisted, “They breached their covenant with the people,” noting that the “ballot is the beginning of democracy, not the end”. In the end, Fahmy assured her, “Egyptians will have the final say in determining their own fate.”

In his meetings on Capitol Hill, Fahmy recalls how Congressmen John Sununu and Jim Moran told him such views then “were not commonly heard in Washington”. To further drive his point in Washington, Fahmy bought from a boutique shop in the same Senate building a “tie that featured the design of the US Constitution”. At the bottom of that design, he says, there was the signature of “We the People”. In typical Hussein Fahmy fashion, the actor proudly wore the tie to a congressional reception. “I wanted to show them how fond we are of the US Constitution, a copy of which also hangs in my house,” he boasts. Along the lines of that constitution, he adds, “I told them the people of Egypt also desire to overthrow the Muslim Brotherhood and wish to choose a government that truly represents them.” Many members of Congress cheered him on and said, “Egyptians should have the right to overthrow Morsi.”

Fahmy demonstrated in the June 30 Revolution and was “proud that Egyptians were exercising their right to change their ruler themselves”. He was frustrated, however, that the US media and some western governments portrayed the revolution as a “military coup”.

He shared his frustrations on Capitol Hill where he attended several hearings and meetings. He asserted to Congress members that this was “not a military coup” because a coup is supposed to be “secretive” and “carried out by the military”. The June 30 Revolution, on the other hand, was “organised and carried out by nearly 30 million people who publicly set the date and time for Morsi to relinquish power”. It was the “people who requested that the military get involved in order to save the country from descending to the chaos of Libya or Syria as they gained their own self-determination”.

Although it has been nearly three years since these events, some US media outlets recently described the current Egyptian government as the result of a “military coup”, as they covered President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi’s recent visit to the United Nations General Assembly in New York. Al-Sisi met with presidential candidates Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump on the sidelines of the General Assembly. Fahmy was closely following the coverage of that visit, as he is the US election.

He flatly admits, “I am against Hillary Clinton.” He criticises the remarks she made during her meeting with Al-Sisi. “She raised concerns about the rule of law and human rights in Egypt,” Fahmy says, describing her remarks as “interfering in another country’s internal affairs”.

Human rights, he notes, “goes both ways.” “What about our soldiers who are being killed daily in the Sinai and other parts of Egypt?” he asks. Al-Sisi, he jokes, “could have responded by telling her to release certain inmates from Alcatraz Prison!” Donald Trump, on the other hand, Fahmy says, “simply praised Al-Sisi and the Egyptians for defending their country”.

The actor believes “Trump will ultimately win the elections,” referring to his wide support among a large sector of Americans who are “fed up with politicians and their lies, unfulfilled promises, and lack of ethics”.Despite Trump’s public mishaps, Fahmy believes that “a figure like Trump remains promising to Americans given he is not from the political establishment”.

However, regardless of who becomes the new president of the United States, Fahmy asserts, “Egypt will always remain a strategic partner and ally.” Fahmy suspects anything would change in US foreign policy, noting that the “military establishment ultimately rules America.”He only wishes that such policy would be “fair”. “It is in the national interest of the US to put its hands in the hands of the Egyptian people under the leadership they elect,” Fahmy states.

For more than 45 years, Hussein Fahmy has been an icon of Egyptian cinema, yet he remains young in spirit. “Some people ask me about my age,” he laughs, “I tell them I stayed 28.” “For me, time is measured in the things you do to make life better for others,” he concludes.