Written by: Mahmoud Demerdash

Date: 2025-12-25

Egypt’s Lost Treasures

Egypt's history is so rich that the absence of certain artifacts might seem negligible amid its vast heritage; however, given the immense cultural and historical value of every piece of Egypt’s past, their loss is deeply and unmistakably felt. For more than a century, some of the nation’s greatest treasures have resided outside their homeland, displayed in European and American museums as symbols of empire rather than integral pieces of Egyptian identity. This reality is particularly poignant today, as Egypt opened the Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM), the largest archaeological museum on earth, to the world. The GEM has become a powerful statement of the country's readiness to reclaim its cultural narrative and celebrate its heritage on Egyptian soil. Yet, many of its most famous artifacts remain abroad, removed during colonial excavations, ceded under questionable ‘agreements’ or simply taken when Egypt lacked the power to resist. Their absence is not just physical; it is an emotional and potent reminder of an injustice that persists to this day from actions taken an age ago. As Egypt enters a new era of cultural restoration and national pride, the conversation around these artifacts has become more urgent than ever, raising critical questions about ownership, identity, and the long journey toward bringing Egypt's lost history back home. There are several notable items currently absent from home that stand out for their importance or sentimental value, and their absence is certainly felt.

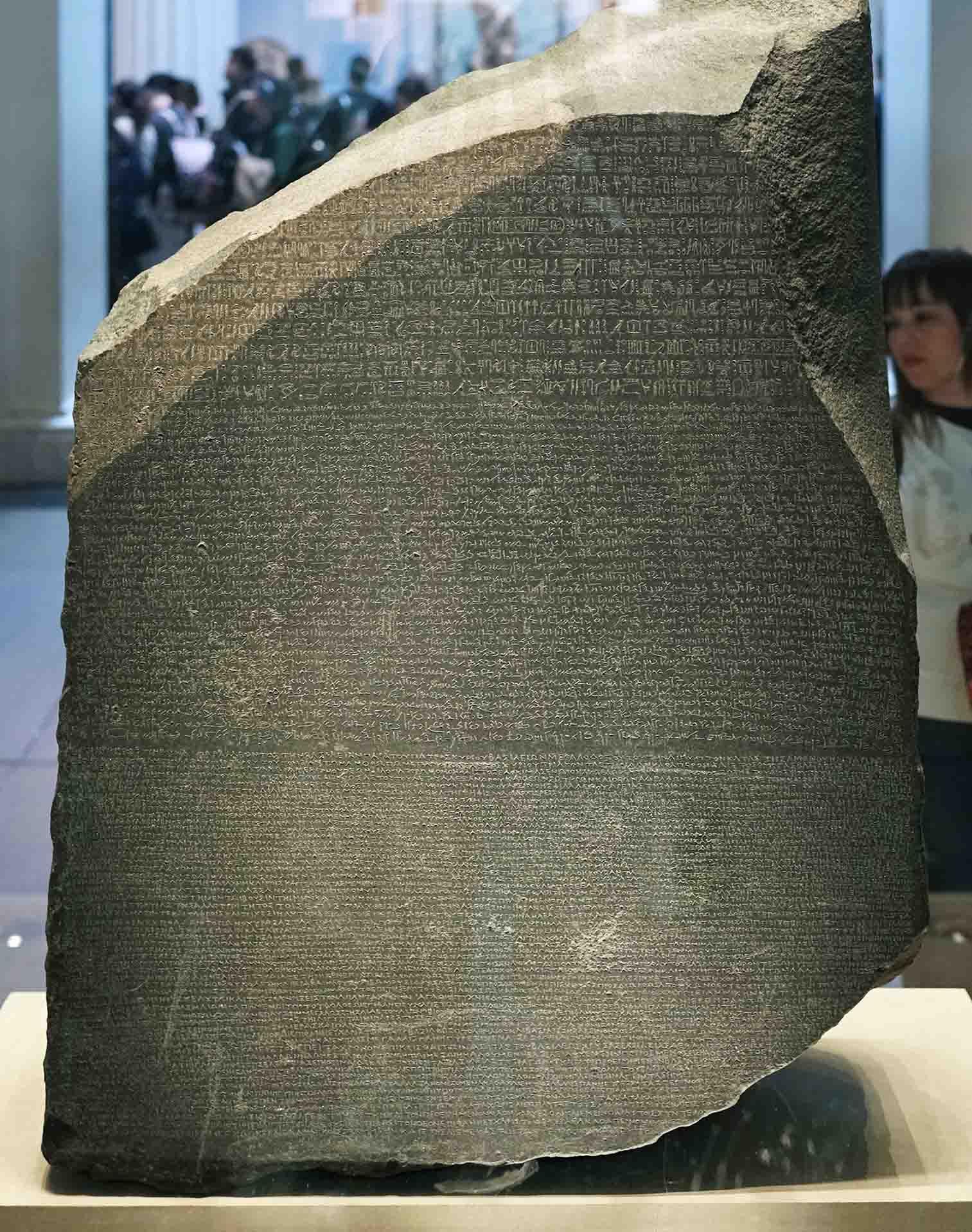

The Rosetta Stone

Discovered in 1799 near Rashid (Rosetta) in the Nile Delta by French soldiers during Napoleon’s campaign, the Rosetta Stone is a pivotal artifact in Egypt’s history. Carved in 196 BCE, it features a decree inscribed in hieroglyphic, demotic, and ancient Greek, a linguistic combination that proved essential for deciphering ancient Egyptian writing. Its discovery revolutionized Egyptology, allowing scholars, particularly Jean-François Champollion in 1822, to finally understand hieroglyphics after centuries, thus granting access to thousands of years of Egyptian records and culture. In 1801, Britain seized the stone from the French under the Treaty of Alexandria and transferred it to London, where it became the most visited artifact and a centerpiece of the British Museum. Egypt has made repeated formal requests for its return, particularly in recent decades. Still, the British Museum maintains that its acquisition was legal; the legality of which is highly questionable, given that it was seized by Egypt during the French occupation and subsequently taken by the French upon their defeat by the United Kingdom and that the artifact should remain part of a ‘universal collection’, a stance Egypt continues to challenge.

The Bust of Nefertiti

One of the most famous ancient sculptures in the world, the Bust of Nefertiti, was discovered in 1912 in Amarna, the short-lived capital city established by Pharaoh Akhenaten. Unearthed by a German archaeological team led by Ludwig Borchardt, the sculpture immediately stood out for its exquisite craftsmanship, lifelike proportions, and vivid colours, features that captured the artistic nature of the Amarna Period. Representing Queen Nefertiti, one of ancient Egypt’s most influential figures, the bust became an iconic symbol of the period’s beauty, power, and artistic mastery. It was taken to Germany shortly after its discovery, under excavation agreements that Egypt has long argued were manipulated or misrepresented, allowing the artifact to leave the country without proper consent. Since the bust of Nefertiti was unveiled in Berlin in 1924, Egypt has repeatedly demanded its return, but Germany has consistently refused. Over the decades, Egypt has tried negotiations, exchanges, political appeals, UNESCO involvement, and even threats to ban German excavations, arguing that the bust was taken under deceptive circumstances and legally and culturally belongs to Egypt. Germany, however, maintains that its export was lawful and now claims the artifact is too fragile to move. Despite renewed campaigns and mounting evidence that the original acquisition was misleading, German authorities and the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation still hold firm, leaving the bust one of the most contested artifacts in the world. Today, the bust is housed at the Neues Museum in Berlin and is one of Germany’s most celebrated treasures, serving as a centerpiece of the museum's identity, despite the artifact having no direct connection to Germany itself.

The Dendera Zodiac

The Zodiac of Dendera, a large carved stone slab displaying the constellations of the zodiac, was discovered by Vivant Denon in January 1799. During his initial visit to the Temple of Hathor at Dendera, Denon entered a small stone chapel on the roof and found the large circular planisphere, or zodiac. Although he lacked time to sketch the artifact then, he returned later that spring to create a drawing, despite the planisphere being part of the ceiling and the chapel being almost completely dark. He published his drawing in his Voyage in 1802. Carved during the late Greco-Roman period, the Dendera Zodiac depicts an intricate celestial map blending traditional Egyptian symbolism with Hellenistic astronomical elements. The Zodiac is considered the earliest known complete representation of the classical zodiac signs in circular form. It offers rare insight into how ancient Egyptians understood astronomy, timekeeping, and their relationship with the cosmos. In 1821, French antiquarians, supported by colonial military presence, sawed the Zodiac out of the temple ceiling and transported it to France. The removal was done without Egyptian consent, causing structural damage to the temple and sparking early controversy about artifact theft. In France, the Zodiac became a sensation. Displayed first at the Bibliothèque Nationale and later in the Louvre, it was celebrated as proof of ancient Egypt’s scientific sophistication and used to elevate France’s cultural prestige during the height of European Egyptomania. In 2022, Egyptologist Zahi Hawass started a petition to bring the ancient work back to Egypt, along with the Rosetta Stone and other artifacts.

The Many Obelisks

Egyptian obelisks, originally honouring pharaohs and Ancient Egyptian gods, are now found worldwide in major cities like Rome, Paris, London, Istanbul, and New York. Many were taken during the Roman Empire as spoils of conquest to decorate public spaces. More recently, the Luxor Obelisk was a 19th-century "gift" from Egypt's ruler, Muhammad Ali Pasha, to France, but the transport and negotiations were highly complex. Similarly, Cleopatra’s Needle was presented to the United Kingdom in 1819 by Muhammad Ali Pasha as a diplomatic gesture, involving costly and dangerous transportation. Today, Rome alone hosts more Egyptian obelisks than modern-day Egypt, with these structures often becoming central landmarks in their new locations, such as the Luxor Obelisk at Paris's Place de la Concorde and London's Cleopatra’s Needle on the Victoria Embankment. The transfer of these monumental structures has generated long-standing controversy, primarily questioning whether they were gifts, diplomatic gestures, or coercive appropriations. For instance, while figures like Muhammad Ali Pasha officially presented Cleopatra’s Needle in London and France’s Luxor Obelisk, critics argue that the asymmetry of power at the time meant Egypt received little tangible benefit and lacked genuine negotiating leverage. The transactions primarily boosted the prestige of foreign nations. The question of whether Muhammad Ali Pasha truly had the authority to ‘gift’ Egyptian obelisks to foreign countries is complex and debated. On one hand, as the de facto ruler of Egypt in the early 19th century, Ali Pasha exercised broad political and administrative power, including over state property, which could consist of monuments like the obelisks. From this perspective, he legally ‘owned’ them in the context of his governance and could make diplomatic decisions involving them. On the other hand, these obelisks were national treasures with deep historical and cultural significance, dating back thousands of years to the pharaonic era. The argument would then be that such artifacts were not the personal property of a ruler, even one as powerful as Ali Pasha, and that their removal deprived Egypt of irreplaceable heritage. In essence, while he may have had legal control at the time, the moral and cultural legitimacy of giving away such monuments is highly questionable.

Should we reacquire? Yes.

With such an immense wealth of ancient artifacts, the question naturally arises: should Egypt reacquire what was taken? Egyptian obelisks stand today in cities across the world; Rome alone has more ancient Egyptian obelisks than Egypt itself, and countless museums rely on Egyptian treasures as the centerpieces of their collections and landmarks. Many of these items are more iconic to their host nations than anything produced by those nations’ own ancestors. The core of Egypt’s argument is straightforward. These artifacts were removed during an era of aggressive colonial expansion, when European powers carved up the world and stripped cultures of their heritage. Egypt is a unique case because its history is unmatched in global influence; its symbols, monuments, and mythology shaped modern pop culture so profoundly that the very field of Egyptology emerged, fueling the Egyptomania that enabled so much of this extraction. Today, with international law, global cooperation, and a more ethical approach to cultural property, meaningful resolutions are not only possible but overdue. These artifacts are more than antiquities, they are symbols of identity, ingenuity, and continuity. They belong among the Egyptian people, inspiring future generations just as they inspired the world.